This Research Insight covers a publication from the Williams Lab. Here, we highlight how Allison Hall and colleagues unveiled the cellular identity of a retinal ganglion cell that innately survives well following injury to the optic nerve. They further explored cellular factors that could help explain the resilience of these cells to offer insights into putative treatments for diseases—such as glaucoma—which stem from damage to retinal ganglion cells.

In their recent paper published in Neural Regeneration Research, scientists in the lab of Philip Williams, PhD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at WashU Medicine, characterize the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) that express GPR88—a previously identified marker for RGCs that are well-surviving following injury to the optic nerve of the mouse retina. Here, Allison Hall—a former post-baccalaureate researcher in the Williams Lab—and colleagues identified ON-responsive direction-selective RGCs (ONdsRGCs) as the predominant population of resilient GPR88-expressing RGCs.

Susceptibility to vision loss following retinal injury and disease

RGCs are a functionally diverse population of cells that encode information about the visual world and send this information to the brain via the optic nerve. RGC types exhibit myriad cellular properties that define how they respond to their visual environment, and these properties also influence their different responses to cellular damage.

While some RGC types are highly resilient and either survive particularly well or show signs of healing and regeneration over time, others are highly susceptible to injury and demonstrate near-complete cell death as a population. Understanding how particular RGC types respond to injury can enable the nuanced identification and investigation of factors that might provide viable treatments to vision-threatening disease—like glaucoma—by either promoting resilience or reducing susceptibility.

The responses to injury of some RGC types are known, but often, the precise identities of the cells that preferentially survive or die following injury have yet to be revealed. Instead, cellular properties—that might be shared by multiple RGC types, including GPR88—have been associated with survival post-injury. Given that these unspecified RGC types can have drastically different responses to injury, in these cases, further investigation is required to elucidate the RGCs that comprise the resilient population and to unlock potential insights into therapeutic opportunities.

In this study, Hall and colleagues enable future mechanistic investigation by characterizing and identifying the RGCs that express GPR88. In doing so, they isolated the RGC type most likely to explain the resilience previously observed in GPR88-expressing RGCs and estimated the survival rates of these cells following injury to the optic nerve.

Disentangling the cellular identities of GPR88-expressing RGCs

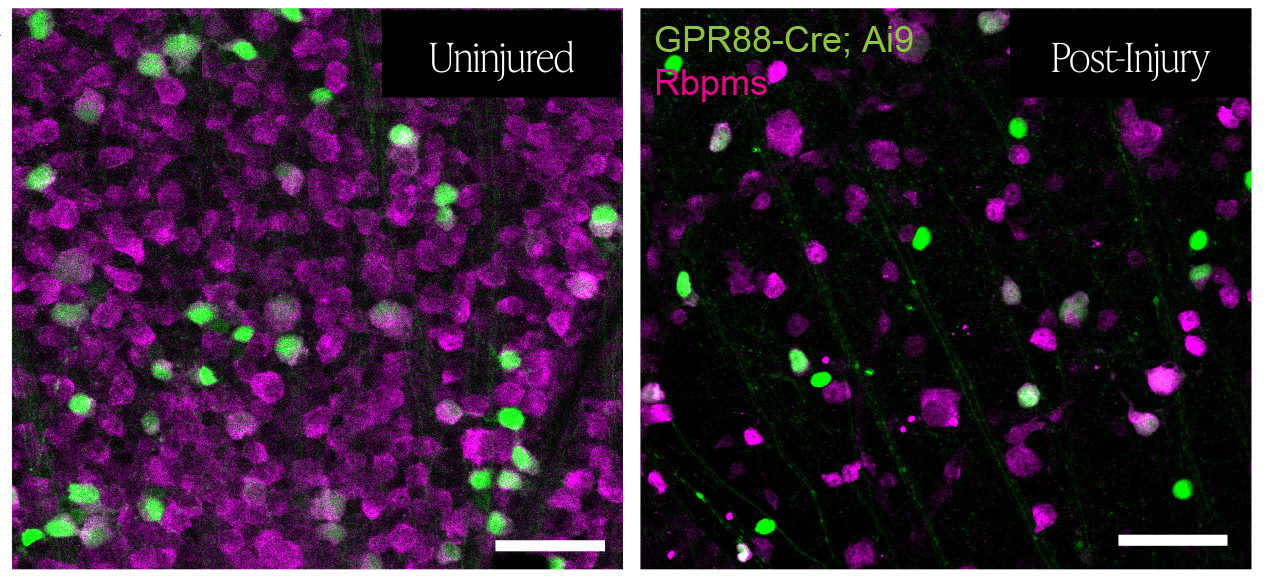

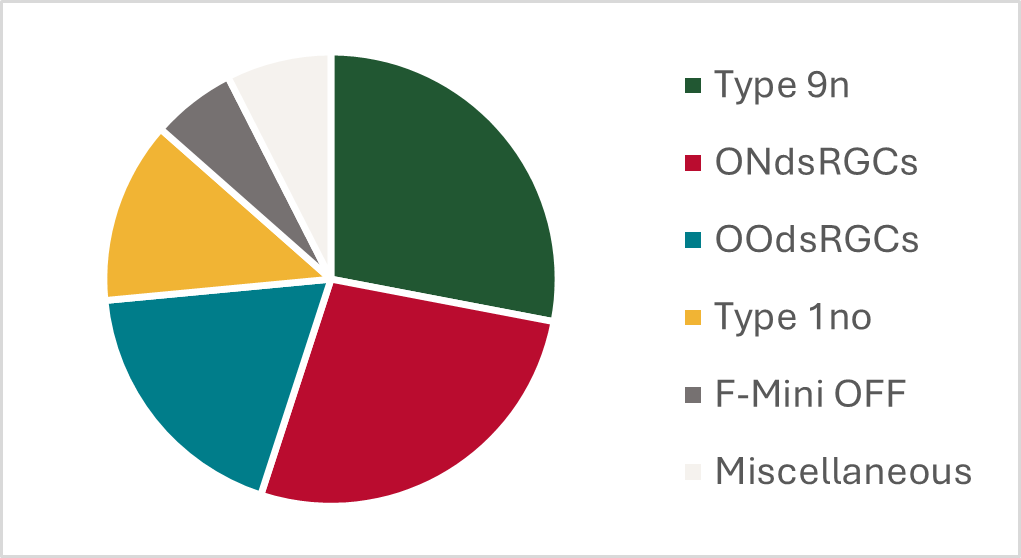

After confirming that nearly all GPR88-expressing cells in the mouse retina were RGCs, Hall and colleagues employed several strategies to uncover their identities. Notably, they utilized a cutting-edge viral labeling tool to sparsely and distinctly label GPR88-expressing RGCs. This viral strategy enabled them to visualize and analyze the structure of the individual RGCs, which revealed that 5 distinct RGC types reliably made up the population of GPR88-expressing RGCs.

The authors validated the identities of these 5 RGC types using targeted antibodies and by identifying the brain areas that receive visual information from the GPR88-expressing RGCs. Each of these experiments was consistent with the 5 RGC types identified based on their cellular structure.

Pinpointing RGC types that preferentially survive following injury

With the identities of the GPR88-expressing RGCs in hand, Hall and colleagues sought to characterize how well each of these 5 RGC types survived following injury to the optic nerve.

The Williams Lab previously showed that high intracellular calcium levels prior to injury can promote the survival of RGCs post-injury. Here, the authors likewise found that the GPR88-expressing RGCs exhibited higher intracellular calcium levels than the full population of RGCs in the uninjured mouse retina. These population-level results are consistent with both a pro-survival role of calcium and the previously reported resilience of GPR88-expressing RGCs. However, Hall and colleagues also observed that the GPR-expressing RGCs exhibited varied intracellular calcium levels, suggesting that the 5 GPR88-expressing RGCs might respond differently to injury.

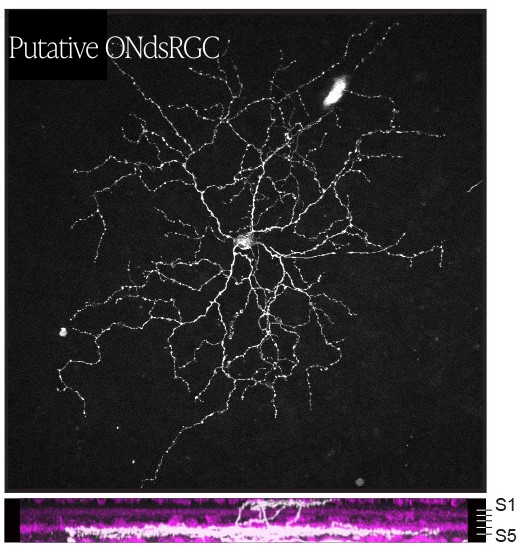

The authors monitored the intracellular calcium levels of GPR88-expressing RGCs after injury and found that the baseline intracellular calcium level of each cell predicted its survival post-injury. GPR88-expressing RGCs with high baseline calcium levels were approximately 3-times more likely to survive injury than GPR88-expressing RGCs with lower intracellular calcium levels. When Hall and colleagues analyzed the structure of the surviving GPR88-expressing RGCs, they discovered that nearly half of the putative ONdsRGCs survived injury and were the most resilient GPR88-expressing RGCs.

Evaluating the potential of putative treatment strategies

Despite the ability of the ONdsRGCs to survive well following injury, Hall and colleagues found that these RGCs did not display enhanced regeneration—or cellular healing—following injury. Instead, they found that the ONdsRGCs retracted some branches of their cellular structure. Even when they applied treatments that have previously triggered limited regeneration in RGCs, the authors found that the ONdsRGCs—and other GPR88-expressing RGCs—did not demonstrate enhanced regeneration compared to other RGCs.

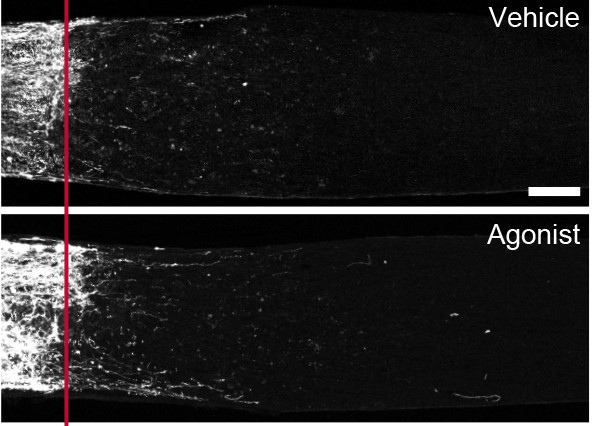

Hall and colleagues instead tested whether compounds that act on GPR88 might protect RGCs from injury-induced cellular damage. They administered these compounds before inducing an injury to the optic nerve and measured the number of RGCs that survived and the density of the optic nerve 2 weeks after injury. The authors could not detect a difference in either metric, suggesting that either GPR88 does not contribute to cell survival, or more than the 5 RGC types identified would require GPR88 expression for a drug to yield a noticeable effect.

Despite these challenges, this study provides valuable insights into how different RGC types respond to injury. Having confirmed the identity of the well-surviving ONdsRGC, Hall and colleagues open the door for researchers to identify novel features of the ONdsRGC that might promote cellular resilience and be used to explore therapeutic opportunities.